In theory, robots may run the US economy one day, but humans still do most of the heavy-lifting in 2025 and for the foreseeable future. Stem the flow of workers into the economy, as Donald Trump has in the first nine months of his presidency, and eventually you’ll gum up the system.

For now, tariffs and high interest rates — as well as uncertainty about the potential of artificial intelligence — are colluding to dampen labor demand, which has allowed policymakers and employers to put off confronting this puzzle. But, in the long run, we’ll pay more for the goods and services we produce, or maybe just create less of them if the US doesn’t take seriously its rapidly aging population and establish policies that guarantee a steady pipeline of workers.

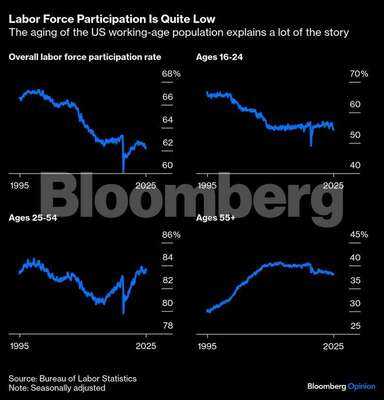

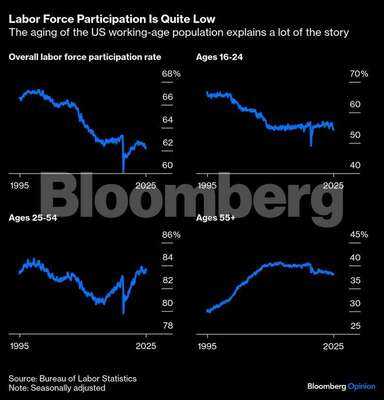

At a very superficial level, there seem to be a lot of would-be workers in the US to draw upon when the time comes. The US labor force participation rate is just about 62.3%, close to a 50-year low, meaning there are about 103 million residents aged 16 and over who don’t currently work and aren’t looking for a job. But luring even a modest number of them off the sidelines is a very tall order.

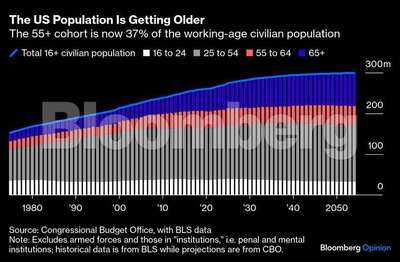

First, consider the 55-and-over population. The aging of the US population appears to be the single-biggest reason that labor force participation has fallen. In the past 20 years, the 55-and-older cohort has gone from about 29% of the civilian populationto around 37%. Its share will increase further in the coming decades, according to CBO projections.

The 55-plus demographic has always participated in the labor force at lower rates than younger cohorts, but the disparity has grown in recent years.

The 55-plus demographic has always participated in the labor force at lower rates than younger cohorts, but the disparity has grown in recent years.

Initially, participation plummeted due to the Covid-19 pandemic. But compositional effects are a big reason that participation has remained low: Proportionally, more and more of the 55-plus group are now over 65. I doubt those folks are coming back to work any time soon. They’ve become quite wealthy thanks to a booming stock market and the surge in home values. Only a reversal of market fortunes could change this state of affairs (and no one should be hoping for that outcome).

As for the 55-64 sub-cohort, their participation is already near record highs even as they rack up similarly impressive gains in the markets, keeping them well situated to become retirees over the next decade or so.

Among the young, those 16-to-24 years old, labor force participation is down significantly since the 1990s. This was partially a positive development, reflecting more kids choosing college. But participation also took a hit from both the financial crisis and the discouraging “no hire, no fire” labor market of the past couple of years. Recent efforts to lure more young people into the trades — instead of four-year colleges — have some potential to lift the supply of labor from this group in a way that could be beneficial for everyone. But a trade-school revolution won’t happen overnight.

Assume an extreme scenario in which this group participates in the labor market to the same extent as it did prior to the financial crisis — rising from the current 54.3% to about 60% — and you get 2.2 million more workers. That would help tremendously, but is it realistic? The 16-to-24 cohort hasn’t seen such a large and sustained increase in labor force participation since the 1970s. A more sensible (but still optimistic) scenario might have participation rising 1 or 2 percentage points, bringing about 400,000 to 800,000 people into the labor force.

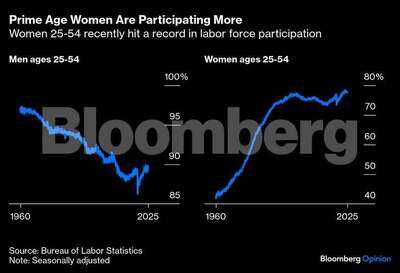

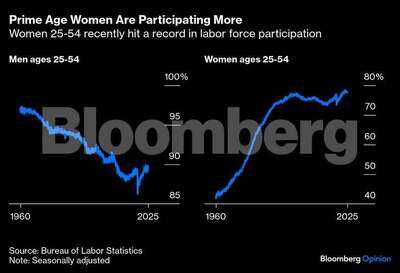

Finally, we have prime-age workers, defined as those 25 to 54 years old. Labor force participation in this group is very close to the record levels attained in the 1990s. There are a few potential levers to pull here before we can say we’ve reached “as good as it gets” — but that will take better child care to help parents get out of the house.

For starters, women: The share of prime-age women in the labor force, at 77.7%, is historically extraordinary and near a record. But it’s still well below the 89.8% of men in the labor force. Closing that gap even halfway would deliver about 3.9 million workers, but it’s an aspiration that’s rendered less realistic by the 28% jump in the cost of day care and preschool since 2019.

Then there are prime-age men. If MAGA labor economics are going to succeed on their own terms, you would expect a renaissance in male participation to be a part of the story. A return to participation rates from the early 2000s would be worth around 1.4 million more workers. What about early 1960s levels? That would get you 4.6 million workers. That’s pretty good, but it’s likely outside the realm of possibility given the ways that society and the economy have changed in the intervening six decades.

Then there are prime-age men. If MAGA labor economics are going to succeed on their own terms, you would expect a renaissance in male participation to be a part of the story. A return to participation rates from the early 2000s would be worth around 1.4 million more workers. What about early 1960s levels? That would get you 4.6 million workers. That’s pretty good, but it’s likely outside the realm of possibility given the ways that society and the economy have changed in the intervening six decades.

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found in a 2025 paper on the drivers of male non-participation that the biggest contributors include men taking on caretaking responsibilities (not a bad thing), men pursuing education into their adult years (also not necessarily bad), and skills mismatches (unfortunate, but addressable through policy). Another body of literature attributes part of the decline to the opioid epidemic, though the causality is complicated (drug addiction and poverty have sadly become a vicious cycle in some parts of America).

This exercise has generously assumed that the existing non-participating population has the skills industry will need if they can be lured back to the job market, but that’s unrealistic. Many people will live in the wrong cities and towns; possess the wrong backgrounds; and lack the proper incentives to take on the jobs that are available.

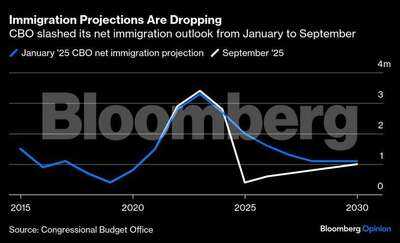

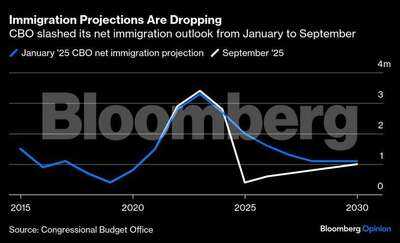

Where possible, policymakers will have to help them acquire new talents and, in some case, relocate to the areas of greatest opportunity. That may became the only option for businesses that need workers to expand. Trump’s effort to dramatically curb immigration flows is set to leave a large hole in the labor market. As of its September update, the Congressional Budget Office now expects about 3.6 million fewer net immigrants from 2025-2030 as it did in January, and other forecasts suggest the drop could be even sharper. The declining immigration outlook is colliding with an aging population and low fertility rates that, try as they might, government officials will struggle to nudge much higher.

AI is the wild card in all this, but the path to AI workplace adoption is likely to be long and winding. Over the medium-term, companies are going to have a hard time getting workers they need as long as immigration flows remain this low — and barring an unforeseen and highly unlikely surge in rates of labor force participation.

AI is the wild card in all this, but the path to AI workplace adoption is likely to be long and winding. Over the medium-term, companies are going to have a hard time getting workers they need as long as immigration flows remain this low — and barring an unforeseen and highly unlikely surge in rates of labor force participation.

For now, tariffs and high interest rates — as well as uncertainty about the potential of artificial intelligence — are colluding to dampen labor demand, which has allowed policymakers and employers to put off confronting this puzzle. But, in the long run, we’ll pay more for the goods and services we produce, or maybe just create less of them if the US doesn’t take seriously its rapidly aging population and establish policies that guarantee a steady pipeline of workers.

At a very superficial level, there seem to be a lot of would-be workers in the US to draw upon when the time comes. The US labor force participation rate is just about 62.3%, close to a 50-year low, meaning there are about 103 million residents aged 16 and over who don’t currently work and aren’t looking for a job. But luring even a modest number of them off the sidelines is a very tall order.

First, consider the 55-and-over population. The aging of the US population appears to be the single-biggest reason that labor force participation has fallen. In the past 20 years, the 55-and-older cohort has gone from about 29% of the civilian populationto around 37%. Its share will increase further in the coming decades, according to CBO projections.

Initially, participation plummeted due to the Covid-19 pandemic. But compositional effects are a big reason that participation has remained low: Proportionally, more and more of the 55-plus group are now over 65. I doubt those folks are coming back to work any time soon. They’ve become quite wealthy thanks to a booming stock market and the surge in home values. Only a reversal of market fortunes could change this state of affairs (and no one should be hoping for that outcome).

As for the 55-64 sub-cohort, their participation is already near record highs even as they rack up similarly impressive gains in the markets, keeping them well situated to become retirees over the next decade or so.

Among the young, those 16-to-24 years old, labor force participation is down significantly since the 1990s. This was partially a positive development, reflecting more kids choosing college. But participation also took a hit from both the financial crisis and the discouraging “no hire, no fire” labor market of the past couple of years. Recent efforts to lure more young people into the trades — instead of four-year colleges — have some potential to lift the supply of labor from this group in a way that could be beneficial for everyone. But a trade-school revolution won’t happen overnight.

Assume an extreme scenario in which this group participates in the labor market to the same extent as it did prior to the financial crisis — rising from the current 54.3% to about 60% — and you get 2.2 million more workers. That would help tremendously, but is it realistic? The 16-to-24 cohort hasn’t seen such a large and sustained increase in labor force participation since the 1970s. A more sensible (but still optimistic) scenario might have participation rising 1 or 2 percentage points, bringing about 400,000 to 800,000 people into the labor force.

Finally, we have prime-age workers, defined as those 25 to 54 years old. Labor force participation in this group is very close to the record levels attained in the 1990s. There are a few potential levers to pull here before we can say we’ve reached “as good as it gets” — but that will take better child care to help parents get out of the house.

For starters, women: The share of prime-age women in the labor force, at 77.7%, is historically extraordinary and near a record. But it’s still well below the 89.8% of men in the labor force. Closing that gap even halfway would deliver about 3.9 million workers, but it’s an aspiration that’s rendered less realistic by the 28% jump in the cost of day care and preschool since 2019.

Then there are prime-age men. If MAGA labor economics are going to succeed on their own terms, you would expect a renaissance in male participation to be a part of the story. A return to participation rates from the early 2000s would be worth around 1.4 million more workers. What about early 1960s levels? That would get you 4.6 million workers. That’s pretty good, but it’s likely outside the realm of possibility given the ways that society and the economy have changed in the intervening six decades.

Then there are prime-age men. If MAGA labor economics are going to succeed on their own terms, you would expect a renaissance in male participation to be a part of the story. A return to participation rates from the early 2000s would be worth around 1.4 million more workers. What about early 1960s levels? That would get you 4.6 million workers. That’s pretty good, but it’s likely outside the realm of possibility given the ways that society and the economy have changed in the intervening six decades. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found in a 2025 paper on the drivers of male non-participation that the biggest contributors include men taking on caretaking responsibilities (not a bad thing), men pursuing education into their adult years (also not necessarily bad), and skills mismatches (unfortunate, but addressable through policy). Another body of literature attributes part of the decline to the opioid epidemic, though the causality is complicated (drug addiction and poverty have sadly become a vicious cycle in some parts of America).

This exercise has generously assumed that the existing non-participating population has the skills industry will need if they can be lured back to the job market, but that’s unrealistic. Many people will live in the wrong cities and towns; possess the wrong backgrounds; and lack the proper incentives to take on the jobs that are available.

Where possible, policymakers will have to help them acquire new talents and, in some case, relocate to the areas of greatest opportunity. That may became the only option for businesses that need workers to expand. Trump’s effort to dramatically curb immigration flows is set to leave a large hole in the labor market. As of its September update, the Congressional Budget Office now expects about 3.6 million fewer net immigrants from 2025-2030 as it did in January, and other forecasts suggest the drop could be even sharper. The declining immigration outlook is colliding with an aging population and low fertility rates that, try as they might, government officials will struggle to nudge much higher.

AI is the wild card in all this, but the path to AI workplace adoption is likely to be long and winding. Over the medium-term, companies are going to have a hard time getting workers they need as long as immigration flows remain this low — and barring an unforeseen and highly unlikely surge in rates of labor force participation.

AI is the wild card in all this, but the path to AI workplace adoption is likely to be long and winding. Over the medium-term, companies are going to have a hard time getting workers they need as long as immigration flows remain this low — and barring an unforeseen and highly unlikely surge in rates of labor force participation. You may also like

Ray announces official retirement from streaming and shares future plans with fans live on Twitch

Migrant wins £40k case after authorities misjudged his age due to 'mature skin'

Chelsea player ratings vs Wolves: Jamie Gittens flourishes in two 9/10s for Blues

Liverpool player ratings vs Crystal Palace: Kerkez struggles again as five stars get 4/10

Arsenal player ratings vs Brighton: Saka shines with four 8/10s in game of two halves